Part One: True Tales

Human against beast is among the most time-honoured story types in the literary tradition, and one that is often carried over into visual representation. The intrinsic survival-oriented aversion to claws and teeth comes from millennia of experience passed down through generations and is ingrained so deeply that the fear of predatory animals seems to be born into human consciousness. When regarding the sensationalism of fantastical creatures, images of dragons and sirens conjure up feelings of awe and excitement, but the real-life presence of domestic and wild animals is a notion arguably fear and fascination inducing. The reality of the world in which we share space with the animal “Other” is filled with uncertainty and enchantment. Often regarded as pure and noble, animals draw in the collective sympathies of people, and are prone to inspire love and admiration for their being. This admiration, however, is occasionally romanticised in light of the underlying mystery that animals represent; dangerous animals are both loved and feared, giving way to a much more potent sense of terror in their presence as compared to other deadly situations. The gravity of the sometimes-deadly encounters between human and animal is a ubiquitous element of adventure stories in art and literature. Collected here are two of the most infamous stories of animal attacks as represented in art.

Brook Watson and the Shark

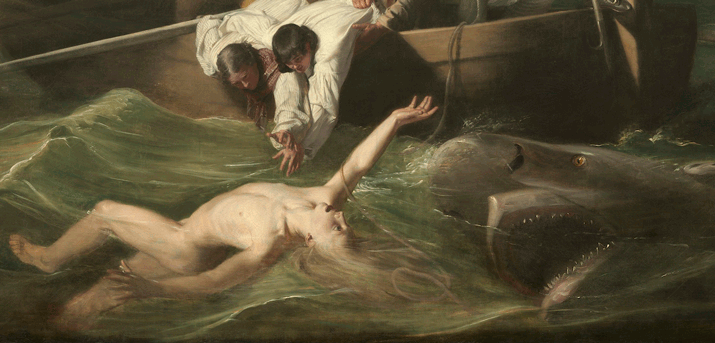

John Singleton Copley’s (1738-1815) painting, Watson and the Shark (1778), depicts the real-life event in which fourteen-year-old orphan Brook Watson (1735-1807) was ravaged by a shark while bathing in Havana Harbour. Watson, who had been working as a cabin boy aboard the Royal Consort, had decided to clean himself in the water just off the skiff of the ship while docked at port in Cuba. The seemingly calm waters, however, were in fact a breeding ground of activity due to the large amounts of food bits that would accumulate where large ships were loading and unloading supplies and cargo. As Watson bathed, he was unexpectedly pulled under by a large shark who rose up from underneath him to take an exploratory bite out of his right leg. The shark retreated for only a few seconds before circling back to take more from the already bloodied Watson, dragging him under again, and this time severing his right foot above the ankle. As Watson surfaced, his shipmates had crowded onto the skiff and were reaching out to him. When the shark propelled towards Watson a third time, one of the ship’s crew managed to fend it off with a boat hook while the others pulled Watson back aboard.

Incredibly, Watson made a full recovery, avoiding infection and other complications after having his leg amputated under the knee and rehabilitating in a Cuban hospital for three months. Watson went on to have a successful military career, working as an administrator for the British Army and acquiring the nickname “the wooden-legged commissary,” after which he directed his career towards merchant operations and later towards politics, eventually becoming the Lord Mayor of London. Ever the well-connected businessman and politician, Watson struck up a friendship with many prominent Americans visiting London, including John Singleton Copley, who was commissioned in 1774 by Watson to paint the ordeal with the shark. Copley created three paintings of the same scene, one housed in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the second in the Museum of Fine Art in Boston, and the third in the Detroit Institute of the Arts.

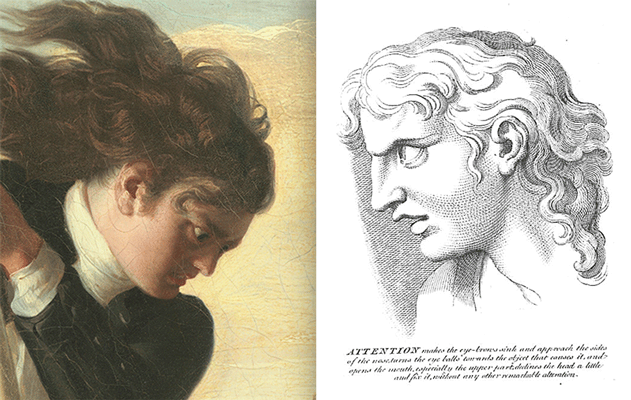

Having produced the paintings based solely on Watson’s description of the event, and with no useful images of a shark to work from, Copley’s rendition of the animal is comically inaccurate. The shark’s round mouth, nostrils, and most notably its forward-facing yellow eyes resemble something more along the lines of a cat or a reptile. Though the painting reflects Copley’s narrow understanding of shark anatomy, the drama and emotional impact of the work surpassed this misgiving. Copley’s success with the paintings lies in his empathetic representation of the emotions as seen on the faces of the men; their expressions range from sadness, to horror, to resolution as they try to save their crewmate amidst the chaos. In light of Copley’s efforts to accurately capture the spirit of his triumph over adversity, Watson bequeathed the paintings in his will to a London school for disadvantaged youth, as a monument to salvation and the ability to overcome disaster.

Hugh Glass and the Bear

Stories of bear attacks in North American culture have reached an almost mythical status, due in no small part to the propagation through art and literature of a few gruesome bear attacks on humans. Globally, freshwater snails kill roughly ten thousand people a year; in North America, a person is much more likely to be injured by a moose or bison than any predatory animal; and in any given year, fewer than two people will die from a bear attack in Canada and the U.S. combined. Though statistically a fatal bear attack is not something to worry about, the sensationalism of a bear attack is undeniably etched into the public’s imagination. This phenomenon is likely attributed to the simple matter of size: a bear is the largest carnivorous land animal in North America, undoubtedly adding to the perception of danger. When the normally peaceful giant among us lashes out with four-inch claws and the strength to pull the roof off a car, the implications weigh heavily on people’s minds.

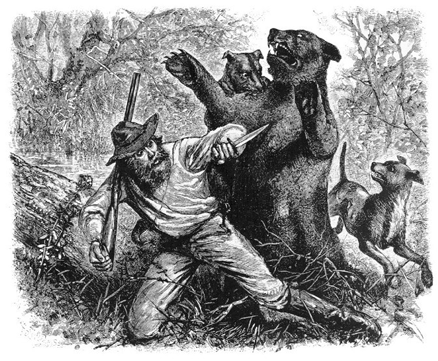

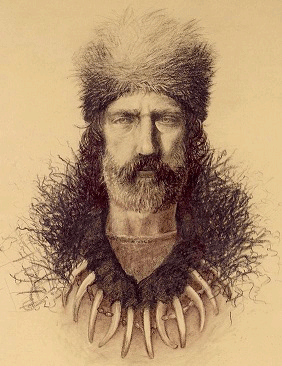

One of the most notorious and culturally significant North American bear attack stories is that of Hugh Glass (1783-1833), an American pirate turned trapper known for his mental and physical strengths as well as his daring and eccentric behaviour. On an expedition to Montana with the Ashley-Henry Fur Company in 1822, Glass wandered away from his group near the Yellowstone River to hunt for food, when he surprised a grizzly sow and her two cubs. Glass was close enough to the mother bear and appeared suddenly enough as to project real danger, causing the bear to charge with clear intent on neutralizing the threat. According to a mountaineer in the group, Glass was “torn to pieces,” and while accounts of the attack vary slightly, the commonality in all versions of the event are that Glass was bitten several times on the head and neck, shaken violently, and raked over his back and legs by the grizzly’s claws before he managed to kill the bear with his knife. The barely living Glass was carried on a makeshift litter by his fellow trappers for three to six days before they decided to leave him for dead on the trail. Despite a broken leg, countless wounds, and exposed ribs, Glass managed to crawl his way back to civilization for more than two hundred miles before reaching Fort Kiowa, where he was treated for his injuries and was able to make a full recovery.

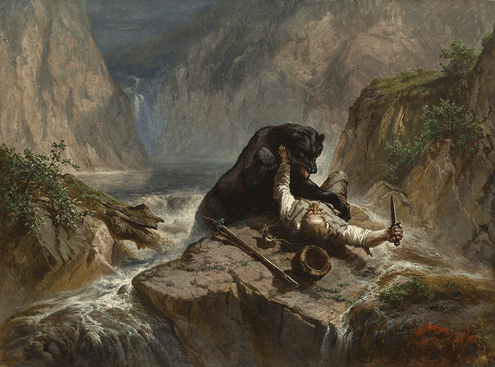

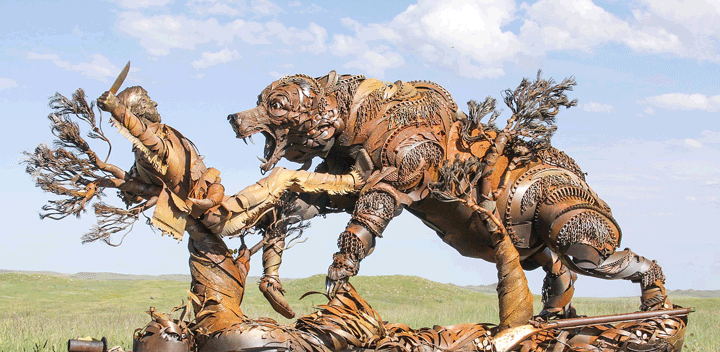

Glass’s encounter undoubtedly spawned a rise in 19th and early 20th-century paintings of bear attacks. Artists like William R. Leigh (1866-1955) and Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait (1819-1905) found relative success in portraying frontier life and the high drama of escape from a predatory bear. American artist Otto Sommer (1811-1911) portrayed a bear attack loosely inspired by the Hugh Glass story in Attacked by a Bear (1862) and American printing company Currier and Ives widely circulated the image of a Hugh Glass-like ordeal in The Life of a Hunter (1861). Today, Hugh Glass is still inspiring artists, with John Lopez’s 2015 multi-media life-sized sculpture, Hugh Glass Monument, Alejandro Iñarritu’s film The Revenant, and pop-surrealist painter Jota Leal’s work, The Hugh Glass Encounter.

The story of Hugh Glass and the bear has been passed down through generations with surprising consistency considering the predominantly oral history of the account. The cohesion of retelling the ordeal is perhaps rooted in the improbability of the event, a story so fantastic that it needs no embellishment. Fictional accounts of animal encounters, however, have also withstood the passage of time, lingering as they do in media output. Coming up in part two: a look at two stories from ancient myth, and the works of art they inspired.