We live in a society with acute concerns of user online safety, the Pegasus Attack being a recent in one of many attacks on people’s privacy, both online and in real life.

On top of this, although online streaming services make it easier for people to access content, it also means that even after paying for the services, people do not actually own any content. And if a service shuts down, like the spectacular failure of Quibi in 2020, all content is lost. Technology, how advanced it may have become, has failed to be sustainable enough.

“So you’re buying a book and you have it on [this device], but you don’t own these things. We won’t own those things anymore,” remarks German installation-artist Aram Bartholl.

Aram’s installation pieces critique technology’s sustainability, or the lack thereof, and its exploitation of people and their privacy.

While thinking of technology’s limitless potential yet very limited recycling techniques, Aram created his sculpture titled How Do You Put Out a Lithium-Ion Battery Fire?

The sculpture utilizes 50 to-be-recycled smartphones mixed with fire-repellant artificial gravel. Recycling old smartphones is a process that causes “massive pollution”. Recycling companies cannot simply give away smartphones because they contain the private data of their previous users.

With more than a billion phones sold in a year, recycling used ones, even storing those to-be-recycled smartphones is a tedious process.

As Aram explains, “lithium-ion batteries pose a threat because they could catch spontaneous fire out of malfunction. This could lead to a whole stack of old phones to go up in flames.”

Tackling the United Nations Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure and Responsible Consumption and Production Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Aram wants people, both developing new technology and buying the technology, to be conscious of the impact their innovations will have on the environment.

“We need to acknowledge that Google and Facebook are purely advertising companies. [...] One thing I’m thinking a lot about is how we can escape the current monopolization of the internet. The web of the ‘90s [...] started as a user-driven, non-commercial space. Over time, many companies and start-ups employed it to achieve their commercial goals, and today we have five or six huge companies, with whom no-one can compete,” says Aram in an interview with Anna Dorothea Ker.

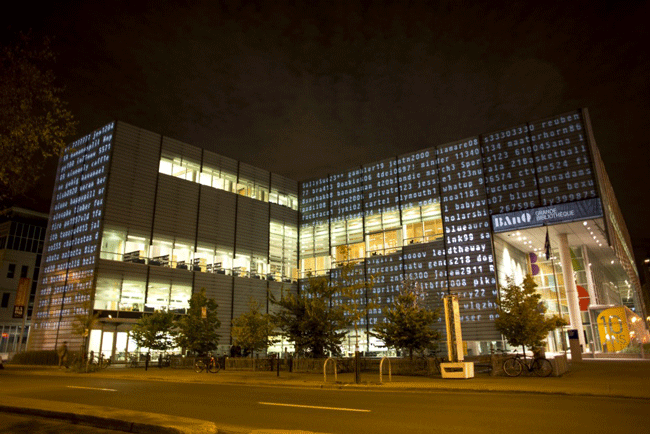

In 2015, Aram exhibited a public installation, titled 123456, of 10,000 leaked passwords from Yahoo in 2012 onto the walls of Grande Bibliotheque in Montreal.

Interestingly, and very unfortunately, Grande Bibliotheque was shut down due to a hacked database in May 2021.

Expressing his concerns about surveillance, Aram says, “Even supermarkets have WiFi tracking systems to see how you pass through the market or and when you return. We are already aware of this on a certain level – for example, when you go into a mattress store and get served advertising from them the next day. But it’s very hard to understand how this works. [...] This is something we should be concerned about, as it’s a wild west out there right now. Companies can basically do whatever they want.”

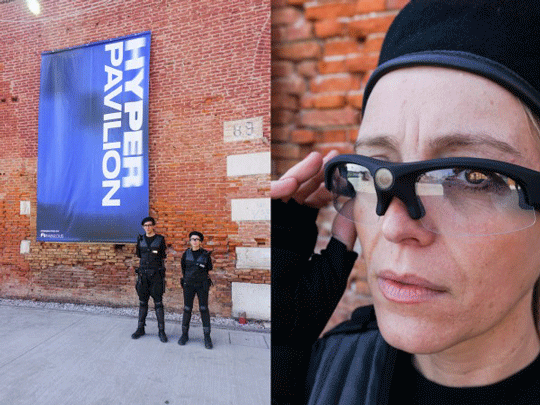

Aram’s evocative performance/installation piece WannCry (Weeping Angels) critiques German government’s latest rules on immigration crackdown. All asylum seekers are required to surrender their phones, which are copied into the government’s systems. Additionally, asylum seekers are forced to show all their social media platforms. Countries like the US already have similar programs, collecting the biometrics of immigrants.

Aram argues, “(w)hen the meta data on your Instagram pictures shows you’ve spent years in Libya, it may be hard to argue that you are actually a citizen of Syria. The difference is that asylum applications from Libya are not accepted (in Germany). It is supposed to be a ‘safe country’.”

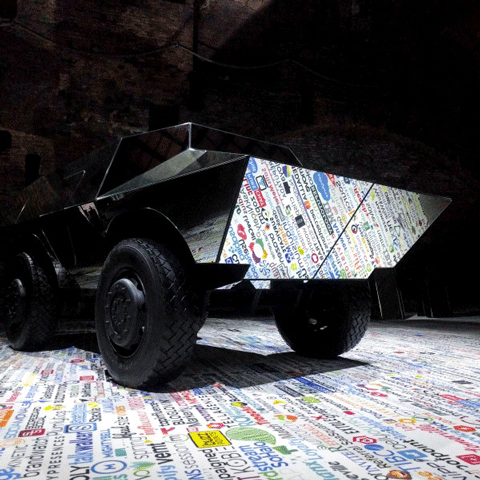

WannaCry (Weeping Angels) consists of an 8×14 meter carpet printed with logos of more than 3,000 internet marketing and user tracking companies. A mirror-covered, disguised, anti-riot police tank is parked on the carpet.

Additionally, ‘specially-equipped’ security guards patrol the exhibition. They hold mirrored shields and question the visitors about their phones: “Is your phone ok? Does you Facebook still work? This is just a security measure for your safety. We had some attacks around here and just want to make sure your device is ok. … All good, thank you. Please don’t turn it off! This will help us to track any suspicious activities.”

Barcodes are stuck on visitors’ phones, which are then scanned by the special unit officer. This is all a pretend-tactic and no actual information is collected from the visitors. However, this visible surveillance greatly unsettles the visitors and forces them to question the invisible surveillance surrounding them at all times.

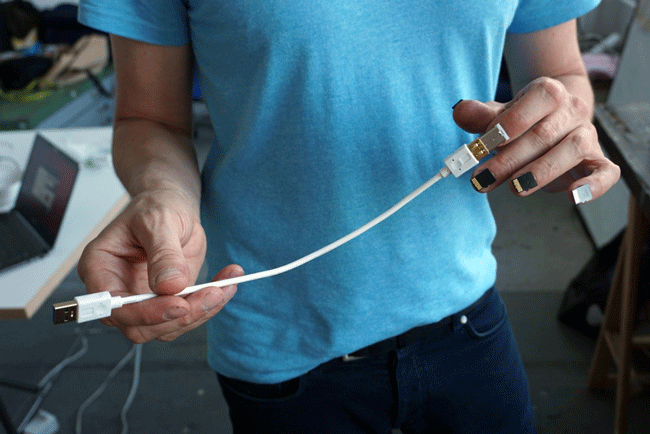

Reflecting on the uproar caused by Edward Snowden leaking classified data in 2013, Aram created a collaborative nail-art piece with Nadja Buttendorf titled Post Snowden Nails.

Each micro SD card contains a vast amount of curated content, totalling to a massive 128 GB.

According to Aram’s website, here’s a brief overview of the data in each card:

Thumb: Live Linux 0S operating system;

Index: 6000 books of Henry Warwicks offline Library 'Alexandria Project';

Middle: A collection of more than 66.000 computer viruses from the virus archive collective VX Heaven;

Ring: The full database of Dead Drops;

Pinky: The full english Wikipedia including the offline reader Kiwix to browse some of the 5 million articles offline.

As Aram remarks, data is literally in a person’s hands.

Henry Warwick, in a video referenced by Aram, discusses how “the online is now precarious; the offline is resilient.”

Henry also argues, “Many people in the 1990s saw the rhizomatic as the model for understanding the internet, where every obstacle is worked around, and where any particular node of the system is destroyed, the rhizomatic system compensated and grows around it. In the past several years, we’ve seen the actual reversal of this. The internet is no longer a rhizomatic structure, but arboretic. Something that can be cut down and hacked to bits and killed.”

To learn more about the Pegasus Attack, check out Amnesty International’s article clarifying details of the software.

For more news on Aram Bartholl’s upcoming exhibitions, check out his website.