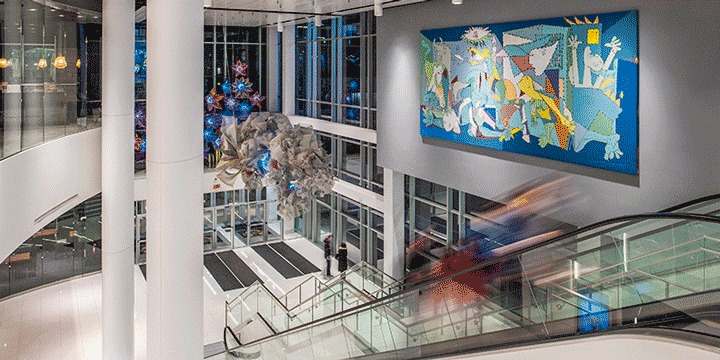

Upon first viewing Viktor Mitic’s paintings, with their saturated colour palettes, flattened perspectives, and tactile surfaces, one might be inclined to perceive the content as playful. The paradox between the lively formal signifiers and the essence of the work, however, speaks to the interconnected and perhaps even co-dependent nature of creation and destruction that the artist has chosen to explore as the opus of his career. One such work is now housed at the Remington Contemporary Art Gallery in Downtown Markham.

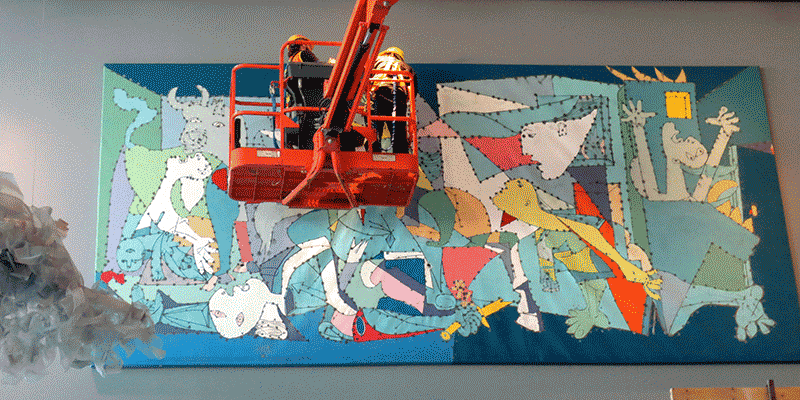

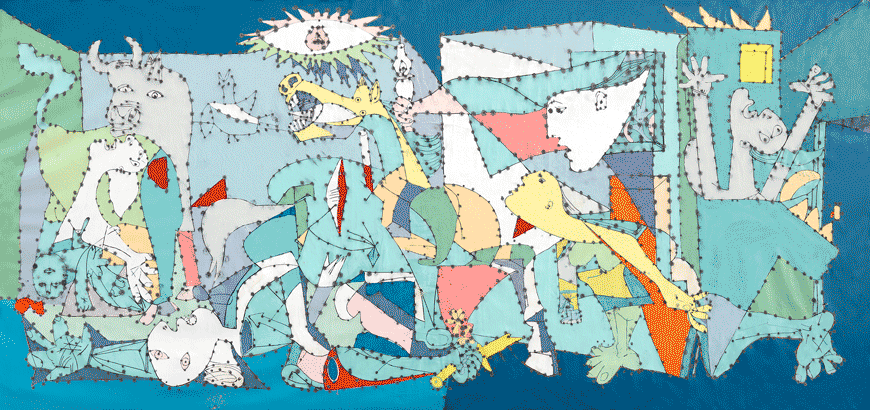

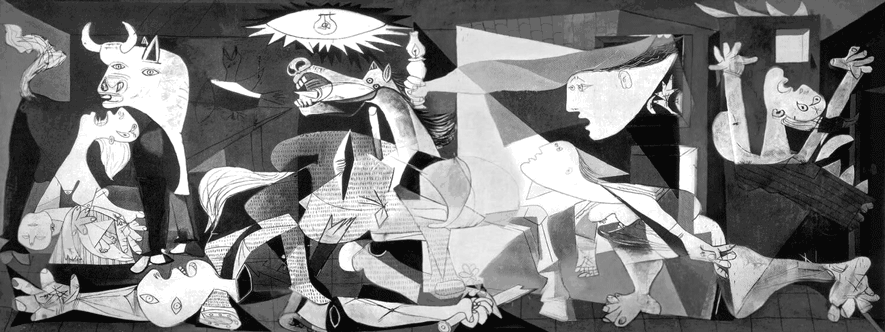

High above the RCAG’s ground floor, overlooking the open space from the mezzanine, sits Blasted Guernica, a painting so large it needed to be installed with a boom-lift. A recreation of Guernica (1937), Pablo Picasso’s (1881 -1973) iconic tableau of war and regarded by many as the most effective anti-war painting in the Western catalogue of art history, at 25 by 11 feet, Blasted Guernica shares the original’s massive scale, but has been updated in ways that the artist perceives as indicative of the contemporary perspectives on war.

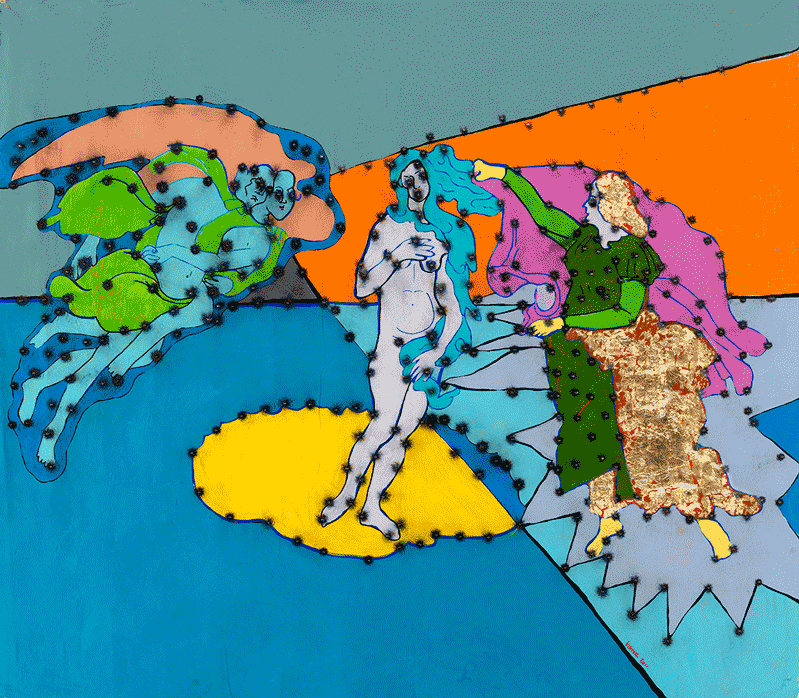

Mitic, a Serbian-Canadian artist based in Toronto, chose the image of Picasso’s Guernica for its illustration of the absurdity of violence, and for its status as an instantly recognizable pillar of artistic creation. The contrast of violence and beauty in art is a continuous source of inspiration for Mitic, whose multi-media artworks blend the visually stunning aesthetics with the jarringly destructive methods by which he finishes his canvases.

Arts Help writer Laura Thipphawong recently met with Viktor Mitic to discuss the meaning of art, controversy, and his work within the RCAG.

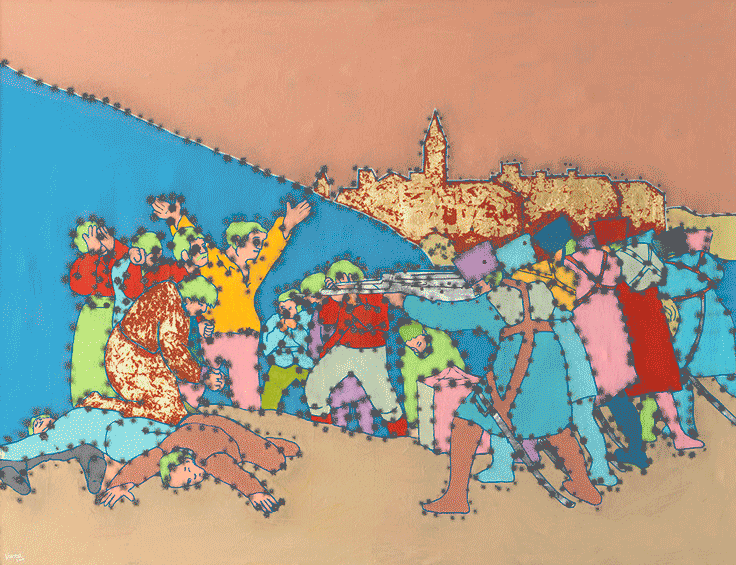

Your work at the RCAG is a recreation of Picasso’s Guernica, considered by some to be his best work for the emotionally charged content as it relates to war. You’ve also done a recreation of Goya’s The Third of May, 1808, another iconic image of war, and like Blasted Guernica, it includes marks made with live ammunition. Why did you choose to propagate these images and why do so with bullets?

I think that those images really work well with what's happening right now all over the planet. The violence is an issue, a huge issue, and I believe that the symbol of the 20th and 21st centuries is the gun. I want to get viewers as close as possible to that reality and I thought I could contribute something by remaking Guernica. I changed the color scheme and brought it into the 21st century by adding bullets and actual bullet holes using the methods of destruction to do something creative.

I’ve done others like this too, one that’s about 26 by 12 feet called D Day All Day. It's a scene of the invasion in Normandy and it's kind of surreal, something that I've been working on since 2007. I think the theme of destruction, art and war has always been interesting to me and I remember seeing videos and photographs on the internet of villages, and soldiers going into certain monasteries and churches shooting up the sculptures and covering their eyes and names. It’s supposed to be almost like some sort of very extreme form of graffiti - making something new of the art by desecrating it. It’s destructive, but at the same time, if you take away all the stuff that is in between the religious aspects, it's actually a pretty intense way of saying something. Graffiti is a softer way of doing the same thing: disrupting.

With violence and destruction playing such a large part in your work, do you feel that your time in the army and your personal experience with war has caused you to form an attachment to the subject matter?

I was in the army when I was 18. It was a mandatory service; I had to be there for a full year and ended up being in Special Forces. It wasn’t my choice, and that was before the war, so it was a Peace Corps, there was no shooting, there was only training for a year and then I moved to Canada, and two years after the war in Yugoslavia broke out. I missed the whole hell and mayhem. I spent my time at the U of T while that was going on. So, I'm not sure if that influenced me, but probably watching the news from time to time would get me to think about what was going on there, but like everybody else here I was feeling pretty detached. That’s the way it is if you're not in it.

Your name is often found in conjunction with the title, Art or War. Can you explain the meaning of Art or War, and is the relationship between art and war the entirety of your work?

That's exactly what is; I’ve tried to transcribe something on canvas, something that was powerful, the romances of war and destruction, on a very peaceful or iconic image, and to subvert them or to disrupt them a little bit. I wanted to add something unexpected that nobody was looking for. The first time I exhibited one of these pieces, the ones with bullet holes, I didn't tell anybody how it was done. It was a secret, and then once someone figured it out then it was on the news and they started talking about it all day long. But for me it was a decorative piece, a decorative element that I wanted to add to the painting. Art or War is a question, but it can be a contrast at the same time. Because they're two different forces working simultaneously. There's no real black and white. It's one big gray area that we're dealing with.

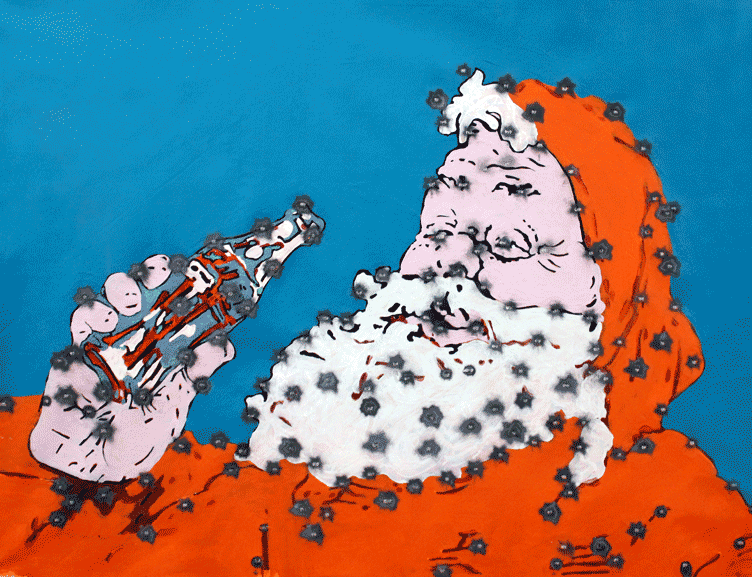

When I had a show in the States, I brought a school bus that had been shot up with bullet holes, and people were shocked that we took it all around Washington DC, in front of the National Mall and all the monuments, and the White House. We forgot to bring signage put on it, so people were freaking out because they thought it was the real thing, but when we told the viewers that it was an art project, they were like, “Oh, yeah, well, that's cool. Let's talk about guns now. What kind of caliber did you use?” People went from being afraid to having fun, almost in the same sentence. One interesting part about that particular pieces was that I had to employ people who were pro-gun to create a message there was against violence. There was no way that I would have been able to get it done otherwise, unless somebody wanted to have fun and shoot thousands of rounds into a school bus. It wasn't easy. It wasn't easy at all to shoot something, like on television, so I had to get people who are into these things, like into shooting and into guns and collecting and whatever, to get them to actually make this piece for me, and it is totally against what they stand for.

What does that kind of duality, or the relationship between beauty and violence mean to you, and why is this a continuing source of inspiration?

There's always this symbiotic relationship between the two. There's always beauty, there's always aesthetics, and there's violence on the other side. Nobody wants to see the violence, but everybody looks at it with a corner of their eyes. Without the violence people wouldn't watch news. There’s no news that’s 100% positive. You go online on a news network and there's only stories of suffering and war. So, combining those two, art and war into one, for me, is the goal, trying to get those two to work together if it's possible. It's up to the viewer to see if it's possible not. I’ve had various comments from critics on both sides and I think that's, that's kind of cool. I think that that should be the way things are, that art should be speaking that way.

There seems to be a fair amount of superficial critique involving a myopic rejection of your work, which forfeits the opportunity for discussion of the broader point. For example, I read a very glib synopsis of your work in which the author refers to you as the “gun-loving artist.” How do you perceive the reactionary negative response to your work and how would you describe your relationship with critics?

I mean, it's up to them to form an opinion, and there're so many of them, some of them love the work, some of them hate it, and that’s normal in any aspect of anybody's life, I think, we can’t all have friends and all on all sides. That would be kind of boring. But it seems like nobody's got more than five seconds, everybody's got ADD right now, and they don't even read, they don't spend time talking to anybody about in-depth analysis of the work and why the artists are doing it. They just pick up whatever's on the surface, they probably pick up a headline somewhere, they see it mentioning the guns and they say, “oh, he’s a gun-loving artist,” without even talking to me. I have encountered that from time to time, but you know, some better publications will go in and actually spend the time talking, analyzing the work and then forming the opinion. But ever since the story broke out that I was working with guns to create those bullet holes, the critiques all became about guns, so it's hard to break through that. It's an uphill battle, but that's why I chose art not some other profession.

I’ve read that you don’t choose to identify yourself as an activist but rather you would like to contribute to a discussion of the sensationalism of gun-culture.

Yeah, exactly like that. I don’t want to be labeled as one or the other. There's no need for that, but I am not pro-gun and I don't own any weapons at all - there's no need for them. But there are so many activists out there talking about the same subject and it all looks exactly the same. They're all repeating the same sentences over and over. I do want to get people to talk about it, but in a different way, and whether they love it or hate it, art can make people talk about a subject. My work can be controversial, but at least there's a conversation that I'm going to push with it.

Is pushing a conversation forward, especially an uncomfortable conversation what you consider to be the purpose of art?

There should be a sense of uneasiness when you come and see a painting, it doesn't matter if it’s a Picasso or a Renoir or any anybody, it should be something that makes you feel something unexpected. For me work, when you see it you did not expect this painting to be shot, for a gun to be used almost like a tool to make a painting, especially one that looks like a connect-the-dot painting (laughs). I was trying to show the whole spectrum of feelings and trying to get the viewer as close as possible to a point where the guns were fired. This is one of the ways of bringing the public as close as possible to something that is not an everyday sight for most people. In real life once somebody pulls that trigger, it's final. That's the end. That's also a very symbolic way of me finishing a painting. I spend like a month a month or two or three, doing a composition, sometimes longer, and then when I take it to a gun range or somebody else's farm, and they shoot it up, that's the end of it, and the painting is finished.

This literal destruction of your work contributes to the reading of it as satirical: an exaggeration or exposure that highlights an absurd aspect of human behaviour. Would you agree with this?

Yeah, exactly, and there's a performative element to what I do also, when I go in and finish the paintings it's usually inside of a gun range with people and guns all around me and here I am with a religious or political painting that some of them might even be against, ad I usually try to do shoot the paintings as quickly as possible because I know that by the end of the session, I'll be kicked out of that gun range. I’ve been kicked out of every gun range in Ontario. It’s ironic, they have targets with human figures, human outlines or even zombies that they're shooting, but an artist comes in and starts shooting a painting and then it becomes an issue. It’s happened to me numerous times: I get in there and I'm drenched in sweat by the time I’m done because I just get through this process as rapidly as possible, ignoring everybody. I just keep on firing until I'm done, and I get out because I know I won't have a second chance. But I have to use these places where people program the act of violence so that I can make this art that is against violence.

Counter to the provocative nature of your work, where would you say aesthetics fall on the scale of importance? In terms of your own work, are aesthetics something you actively think about?

The aesthetic is very important, something that has no artistic form is just a statement; it takes you to one side and I don't want to walk on that side, so the aesthetics is what I'm looking for on top of the meaning. At the end of the day, when I finish the painting, I might shoot it or I can run over it with a car, I can do whatever I want but it’s got to look good. I went to school for art and spent years training and I more or less know what I need to do in order to get the look I want, what elements in composition, and color combinations that I want to use to get something to stand out the way I want it to.

Much like your work, the curation of the RCAG’s collection blends the visually pleasing with topical. Circling back to Blasted Guernica as one of the more challenging pieces in the collection, what do you hope that people take away upon viewing this work?

That’s hard to say. I hope it’s a piece that’s powerful enough to be noticed, and I think the scale is right for that space, and it's in a very prominent spot. I shouldn't be telling anybody what to think, right? I don't know if I'm gonna be that important in anybody's life to make them form an opinion on any given subject, but if they notice the painting and the interplay, the way I work with the lines and the original composition of Picasso… let me think about it.

As far as how it fits in at the RCAG, Shelley Shier was the curator of the gallery and we met back in I think 2012 or 13 when I had that painting exhibited at the Toronto Art Fair. It was the biggest painting ever exhibited over there. It was so big that people didn't even actually notice it, they would just walk you right by it. But Shelley saw it and immediately started a conversation. She’s just amazing, the way she actually put all these pieces together, kind of merging into one theme that is actually just bursting with life.

About the piece individually, it doesn't matter what I want to say exactly. This is just something I do because of some specific urge, like the crazy streak in everybody I guess, and this is how I go for it, I create something to destroy it a bit, but nobody's gonna see that part of it. They're seeing a large two-dimensional piece on canvas with bullet holes carefully selected. And I hope they make something more of it and think about violence and what needs to be done. Ideally it should be a more complex reaction, but at the same time, I strongly believe that the piece of art at the end should look good. It doesn't matter how it's done as long as the end product is strong.

Viktor Mitic

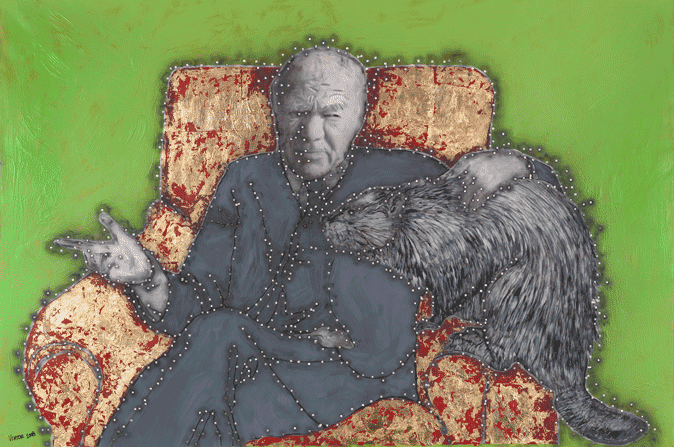

Viktor Mitic is a Toronto-based painter and sculptor who came from the former Yugoslavia to Canada to study art at the University of Toronto. Mitic started receiving recognition for his portraits of Canadian political figures such as Jean Chrétien and Stephen Harper, the latter a derogatory statement entitled Screw Harper was created with common screws and featured in an exhibition called “Art of Deconstruction'' at Pages Bookstore in Toronto. The brazen pairing of subject and media gave way to Mitic’s most famous and overarching body of work which he calls Art or War, a series of paintings involving the juxtaposition constructively creating art, and the destructive act of violence as represented by the use of bullet holes in the canvases. Mitic, though he chooses not to identify as an activist, seeks to contribute to the sobering discussion of violence as integral in pop-culture, and the absurdity of commodifying death and tools of destruction.