Since the moment she could grasp a brush, Penda Diakité was determined to be an artist. Diakité grew up in her parents’ art studio - her father was a storyteller and ceramicist, her mother, a sculptor - and it proved fertile ground for her talent. As a four-year-old, Diakité learned traditional bògòlan painting. In elementary school, she began experimenting with movies and short films. At ten, she published her award-winning book I Lost my Tooth in Africa. Her experience with different artistic mediums eventually culminated in a diverse and lucrative career - today, Diakité has displayed her work in four exhibitions, participated in eighteen film screenings, and runs her own clothing line.

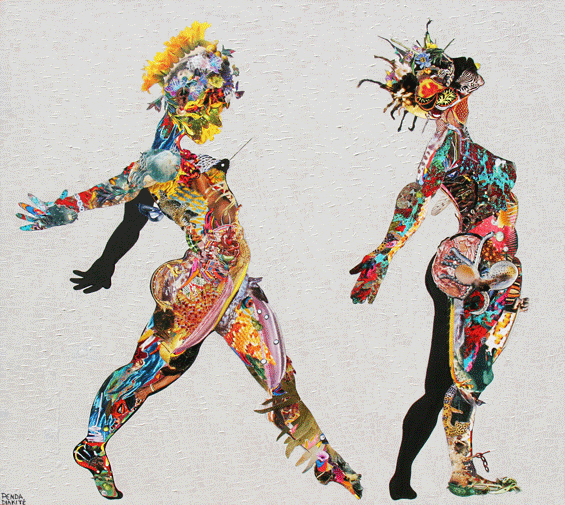

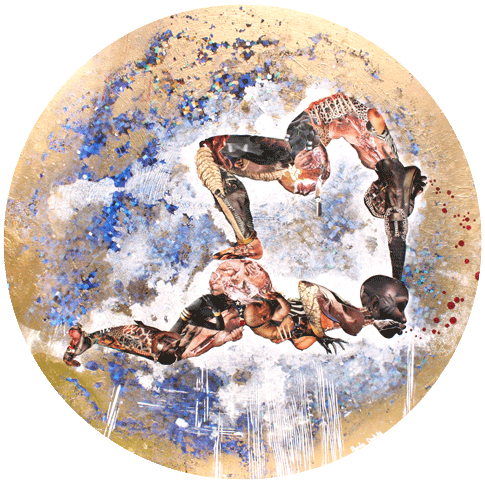

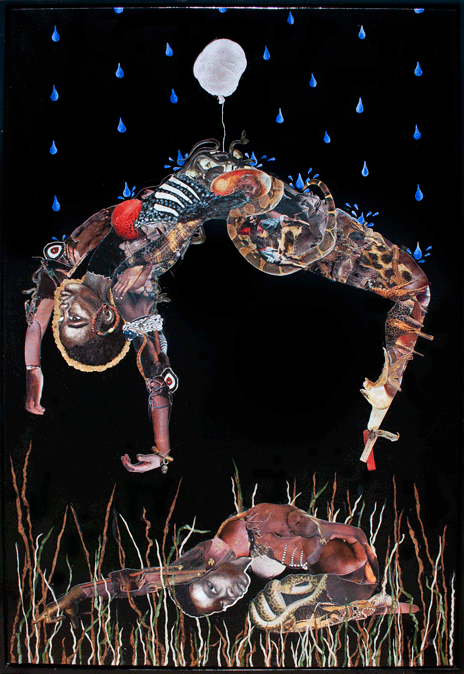

Diakité is a force of nature, and many of her pieces are based on the balance between humans and the natural world. Her works are a vibrant collage of different mediums: acrylics, spray paints, and oils. Specifically, Diakité’s work focuses on breaking down stereotypes that surround black women in the 21st century. Her pieces are influenced by the women around her; she draws inspiration from her maternal line, including her grandmother and aunts. Diakité focuses on the beauty that is inherent in all African women, and nowhere is this more apparent than her upcoming show, Mousso-ya. Located in L.A, Mousso-ya will run from September 12th to 10 October 10th, 2020, and places special emphasis on "If our soul's experience was reflected in our appearance." Earlier this month, Arts Help Writer Rachel Ezrin sat down with Diakité to discuss womanhood, strength, and of course, Mousso-ya.

What is Mousso-ya? What was the inspiration behind the exhibit?

Mousso-ya means “womanhood” in Bambara. Bambara is the native language of Mali, where my father’s side of the family is from. In Bambara the word Mousso-ya – it really represents everything that contributes to the strength of a woman. That’s really what this show is about – it’s about the strength of black women in this world. You know, we’re mothers, sisters, friends. We bear and nurture life. The show’s about the inner and outer beauty of black women.

The definition of womanhood has drastically changed over the past few decades. How do you define womanhood? How is it apparent in Mousso-ya?

This body of work is focused on the strength and power that black women hold. That’s always been consistent throughout history – as far as being leaders and being the backbones of families and kingdoms and being survivors. That’s the truth I stick with throughout all of these pieces.

But of course, you look in the past and present and there’s a whole wide array of expectations. I illustrate those aspects in my work, but in this particular collection, I’m really focused on that constant of the strength and the beauty that we hold.

Can you tell me how these themes of strength and beauty are apparent in Mousso-ya?

If you look at the pieces, almost all of them are figures. It’s about the images that the figures are made up of. I’m using a lot of images that represent my heritage back home in West Africa and the beauty of brown skin. The beauty of little details in our culture. For example, the fabrics that we use and the traditional patterns that we have. For example, bògòlan, which is a traditional mud cloth, fabric, and pattern. Just different aspects of the culture that represent beauty to me. Images of mothers – which, I think is the most beautiful thing – nurturing and bearing life. So, images like that make up all of these figures are really what’s representing beauty.

How has your identity affected your work? Has it influenced Mousso-ya?

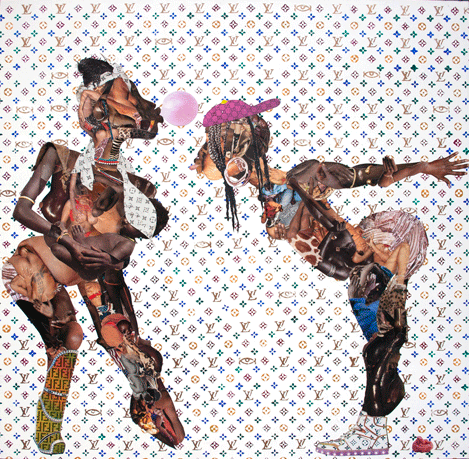

My work has always really been a total reflection of my identity….Each piece is a reflection of a black woman in the modern world. It illustrates these blended cultures of my West African heritage with my American heritage. I grew up between Mali, West Africa and Oregon. I illustrate that in my artwork. All of my creations are really about identity, specifically, black feminine identity.

I’ve been working through this idea that if our souls’ experience was reflected in our appearance. As I was describing the pieces before, each figure is made up of different images that illustrate the characters’ thoughts, emotions, and life experiences. That really plays into [this idea]. Each figure is made up of small cut-outs that represent each character. Each of the cut-outs represents concepts that shape the individuality of black people today. Past and present stereotypes and culture – and popular media’s portrayal of people of colour.

You mentioned that you’ve been experimenting with this concept of “The soul’s experience was reflected in our appearance.” Can you tell me how you came to this realization of this concept and incorporated it into your work?

That’s actually an interesting question! I haven’t really thought about it! I haven’t really thought about where this idea was born. When I started my mixed media work, it was kind of a natural thing to go to. And I think that’s because, you know, when I originally started and still today, you know, all of my work is my expression – a direct reflection of myself. They’re all self-portraits in a way. So, I would gravitate towards images that I resonated with, that spoke to me. And I started creating figures and it kind of grew into that idea.

I did it, and then I realized what I was doing. I realized that I was creating images that were a reflection of me. As I grew as an artist and continued to create, it really gave a voice to our experience as black women in general. It grew into that idea.

Are there any women that have influenced your work?

Definitely! Lots of women in my family [influenced my work.] Growing up partly in Mali, all of my aunts and cousins that surrounded me played a big role in who I am today as a woman. My grandmother – one of the strongest women that I know – she was a single mother raising seven children in Mali. Just knowing her, and knowing the strength about her, and knowing what I was connected to, has really been influential to me. And, of course, her daughters are just like her!

Just honestly, women in general over there [inspire me]. There’s just a strength to everyday life. When I’m over there, every day we wake up and walk a mile to the market, get all the groceries, and bring them back on a huge bucket on our heads. Just the strength of everyday tasks are very beautiful and inspiring to me.

What do you want people to take away from Mousso-ya?

The pieces are an honest reflection of my experience as a black woman. All the characters are made up of images that reflect what it means to be a black woman in modern-day America. A lot of the characters are made up of images reflecting us as mothers, daughters, wives, and caretakers. As human beings. But the images also reflect the hardships and struggles that we endure and the huge amount of strength that it takes to deal with systematic sexism and racism in our country. In these characters, there are also references to my West African heritage where my roots are. So just images that reflect the beauty, of my heritage next to all these different types of images. Images of stereotypes that are constantly perpetuated in modern-day popular media.

I’m also putting images of different stereotypes in my work because I feel like this is something that really affects us as women and how we see ourselves. We can really internalize images, and this affects how we treat each other, and how others see and treat us as well. Some of the pieces in this collection are a lot lighter – [they’re] celebrating the beauty of black women as a being. In my culture in Mali, I grew up with this idea that everything’s interconnected with everything in nature. Just like symbiosis, we need everything to live: from plants to animals. It’s a very nurturing culture. We’re really taught that we have to love and nurture everything and everybody around us. Many of the figures are created with images of nature as well. Like plants, and animals, to really embody that traditional, West African ideal.

How do you break down stereotypes through your art?

In my art, each figure is made up of different images, and they’re all interwoven and interconnected as if they’re one. I have different images of, for example, the brown female body. [They’re] kind of more hypersexualized images. But then, also, next to images of a woman breastfeeding. So really kind of breaking it down in that way of what the body is. And how it can be portrayed and viewed and skewed in different ways for different messages. The black female body throughout history has been very hypersexualized, so that’s something I illustrate a lot in my work.

Have recent events – like the Black Lives Matter Movement – influenced Mousso-ya? If so, how?

As far as the BLM movement, I would say, for brown and black people, it’s been a lifelong fight. It’s something we’ve always been fighting for our whole lives. The only thing new is that now it’s gaining traction. People are starting to pay attention to it. I would say [it’s] more about my life’s fight and my life’s experience. Growing up around other similar experiences has always played a role in my pieces. Since they’re all images that reflect me and women of colour. All my pieces are an expression of me, so naturally, that fight is reflected in there.

You’ve had an exciting life! You grew up in Mali and Oregon, published a book at ten, and run your own fashion line. What’s next for you?

Overall, I’m blessed and lucky to be doing what I love. Honestly, I plan on continuing to create and continuing my artistic journey.For more information, visit @thebeautifulartist on Instagram and Penda’s website PendaDiakite.com.